What Effect Did the Black Plague Have on Art

What plague art tells us most today

How have artists portrayed epidemics over the centuries – and what can the artworks tell the states near then and now? Emily Kasriel explores the fine art of plague from the Blackness Death to electric current times.

A

Every bit their communities grappled with an invisible enemy, artists accept often tried to make sense of the random devastation brought by plagues. Their estimation of the horrors they witnessed has changed radically over time, just what has remained constant is the artists' want to capture the essence of an epidemic. Through these artworks, they have recast the plague as something not quite as amorphous, unknowable, or terrifying.

More similar this:

- The symbol that sums up our times

- What do our dreams mean?

- The plague writers who predicted today

Throughout virtually of history, artists accept depicted epidemics from the profoundly religious framework within which they lived. In Europe, fine art depicting the Black Death was initially seen as a warning of punishment that the plague would bring to sinners and societies. The centuries that followed brought a new role for the creative person. Their task was to encourage empathy with plague victims, who were later associated with Christ himself, in order to exalt and incentivise the courageous caregiver. Generating strong emotions and showing superior strength overcoming the epidemic were means to protect and bring solace to suffering societies. In modern times, artists have created cocky-portraits to show how they could suffer and resist the epidemics unfolding around them, reclaiming a sense of agency.

Through their creativity, artists have wrestled with questions about the fragility of life, the relationship to the divine, as well as the role of caregivers. Today, at a time of Covid-19, these historical images offer us a run a risk to reflect on these questions, and to ask our ain.

Plague every bit a warning

At a fourth dimension when few people could read, dramatic images with a compelling storyline were created to captivate people, and print them with the immensity of God'south power to punish disobedience. Dying of the plague was seen not simply equally God's penalisation for wickedness but every bit a sign that the victim would endure an eternity of suffering in the globe to come.

This early on illustrated manuscript depicts the Black Decease (Credit: Courtesy of Louise Marshall/ Archivio di Stato, Lucca)

This epitome is one of the starting time Renaissance Art representations of the Blackness Decease epidemic, which killed an estimated 25 million people in Europe during its well-nigh devastating years. In this illustrated manuscript painted in Tuscany at the end of the 14th Century, devils shoot downwardly arrows to inflict horror upon a tangled mass of humanity. The killing is portrayed in existent time, with one arrow nearly to hitting the head of i of the victims. The symbol of arrows as carriers of disease, misfortune and expiry draws on a rich vein of arrow metaphors in the Old Testament and Greek mythology.

Australian art historian Dr Louise Marshall argues that, in illustrations like this, devils are subcontracted by God to castigate humanity for their sins. Medieval people who saw this image would be terrified by the winged creatures because they believed devils had emerged from the underworld to threaten them with incredible powers.

This portrayal shows u.s. the devil's slaughter every bit indiscriminate, emerging out of the corrupted temper of the dark clouds to target the whole community. "The image acts as a alert almost non only the loss of a community but the terminate of the earth itself," says Dr Marshall. In this agreement of the plague, the apocalypse is laid on for humanity's ultimate benefit, so that we can acquire the error of our ways and fulfil the divine will past living a true Christian life.

Plague is portrayed as a penalization in this 14th-Century illustration (Credit: Rylands Library/ University of Manchester)

The plague punishment narrative also forms function of the story of the liberation of the Jewish people from Egypt, retold by Jewish communities every year at Passover. This image of one of the 10 plagues brought down on the guilty Egyptians comes from a 14th-Century illuminated Haggadah. The manuscript was commissioned by Jews in Catalonia to employ at their annual Passover repast. Here, the Pharaoh and one of his courtiers is smitten past boils for their sins of oppressing the Israelite slaves who the Egyptians claimed were swarming like insects. Professor of religion and visual culture, Dr Marc Michael Epstein, highlights "the farthermost punishment revealed in the detail of this paradigm, the three dogs licking their sinful Egyptian owners' festering sores".

Artworks created during times of plague reminded even the most powerful that their life was fragile, temporary and conditional. In many plague paintings there is an emphasis on the suddenness of decease. The prototype of the d anse macabre is repeated, where everyone is encouraged by the personification of death to trip the light fantastic to their grave. There is also extensive apply of the hourglass to warn believers that they had just limited time to get their affairs and souls in order earlier the plague might cut them off without alarm.

Plague inspiring empathy

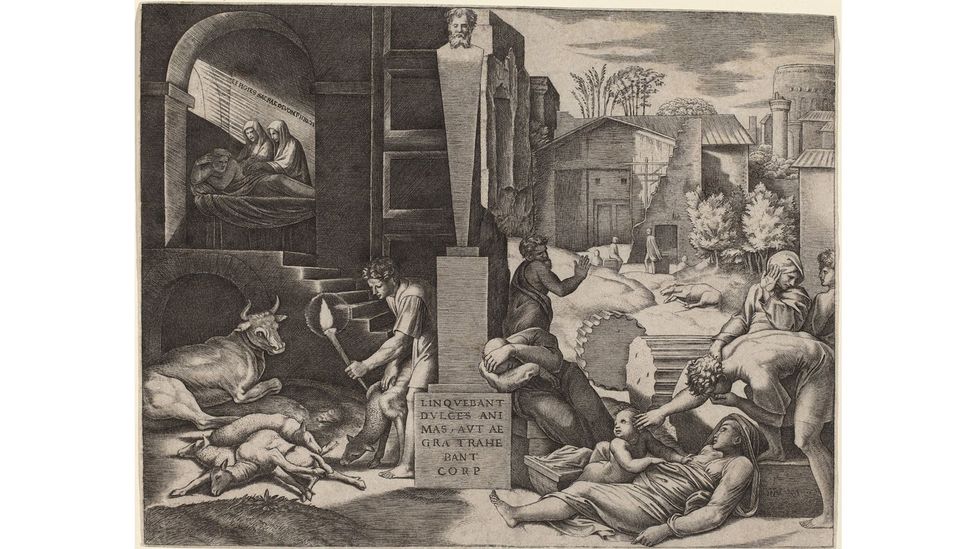

At that place was a dramatic evolution in plague fine art with the creation of Il Morbetto (The Plague), engraved past Marcantonio Raimondi in the early 16th Century, based on a work by Raphael.

This 16th-Century engraving is by Raimondi (Credit: The National Gallery of Art Washington DC)

According to US plague fine art historian, Dr Sheila Barker, "what is significant virtually this tiny image is its focus on a few individuals, distinguished by their age and gender". These characters have become humanised, compelling us to feel compassion for their suffering. We run across the ill existence given such tender intendance that we feel we too must human activity to relieve their pain. Here, a work of art has the potential to convince united states of america to do something we may exist afraid of doing – taking care of diseased and contagious souls.

This shift in plague art coincided with a new understanding of public health. All members of society deserved to be protected, not just the wealthy who could escape to their country villas. Doctors who fled the city for their ain condom were to exist punished.

This empathy theme was further adult in the 17th and 18th Centuries, with the closer alignment of the Catholic Church with a public-health agenda. Plague fine art began to exist displayed inside churches and monasteries. Sufferers of the plague were now associated with Christ himself. Dr Barker argues that the purpose behind this identification was "to convince the friars to overcome their fright of the putrid scent of the dying torso and the immensity of death by learning to love the contagious victims of the plague". Those who cared for the sufferers potentially sacrificed themselves and were therefore exalted by being portrayed as saint-like.

Poussin painted The Plague of Ashdod in 1630-31 (Credit: DEA / G DAGLI ORTI/ De Agostini via Getty Images)

Healing power

In the 17th Century, many people believed that imagination had the power to harm or heal. The French artist Nicolas Poussin painted The Plague of Ashdod (1630-1631) in the middle of a plague outbreak in Italy. In a recreation of a faraway tragic biblical scene, which provokes feelings of horror and despair, Dr Barker believes that "the artist wanted to protect the viewer against the very disease the painting depicts". Past arousing powerful emotions for a distant sorrow, viewers would feel a cathartic purge, inoculating themselves against the anguish that surrounds them.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi's 1892 artwork shows a warrior resisting smallpox demons (Credit: National Library of Medicine)

The plague of smallpox devastated Japan over many centuries. An artwork created in 1892 depicts the mythical Samurai warrior Minamoto no Tametomo resisting the 2 smallpox gods, variola major and variola pocket-size. The warrior, known for his endurance and fortitude, is portrayed as strong and confident, clothed with viscerally red ornate garments and armed with swords and a quiver full of arrows. In contrast, the fleeing, frightened, colourless smallpox gods are squeezed helplessly into the corner of the image.

Navigating hurting through the cocky-portrait

Modern and contemporary artists have created self-portraits to make sense of their own plague suffering, while simultaneously contemplating the transcendent themes of life and decease.

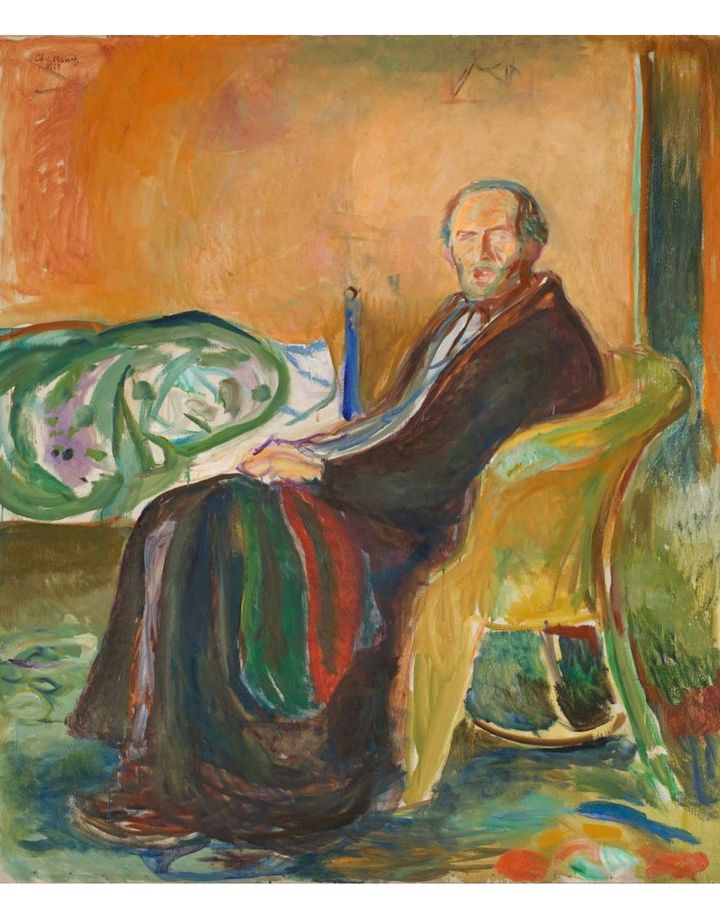

Edvard Munch's Cocky-portrait with Spanish Flu (1919) expresses the artist's own hurting (Credit: Nasjonalmuseet/ Lathion, Jacques)

When the Spanish Flu hitting Europe just after Earth War One, Norwegian artist Edvard Munch became one of its victims. While his body was nonetheless grappling with the flu, he painted his trauma – stake, exhausted and lonely, with an open up mouth. The gaping oral fissure echoes his most famous piece of work, The Scream, and mayhap depicts Munch'south difficulty breathing at the fourth dimension. There is a strong sense of disorientation and disintegration, with the figure and furniture blending together in a delirium of perception. The creative person's sheet looks similar a corpse or a fitful sleeper, tossing and turning in the dark. Unlike some of Munch'southward previous depictions of illness, in which he portrays the sick person's loved ones waiting with anxiety and fright, the artist here portrays himself as the victim, who has to endure this plague isolated and lone.

U.s. bookish Dr Elizabeth Outka tells BBC Culture: "Munch is not just holding a mirror to nature, but also exercising some command through reimagining it." Outka believes that art serves as a coping mechanism hither for both the creative person and viewer. "The viewer may feel a profound sense of recognition and pity for Munch's suffering, which tin in some way help to heal their distress."

Egon Schiele's The Family, 1918, is full of anguish (Credit: Fine Art Images/ Heritage Images via Getty Images)

In 1918, Austrian artist Egon Schiele was at piece of work on a painting of his family, with his pregnant married woman. The small kid shown in the painting represents the unborn kid of couple. That fall, both Edith and Egon died from the Spanish Flu. Their child was never built-in. Schiele attached great importance to cocky-portraits, expressing his internal anguish through eccentric body positions. The translucent quality of skin is raw, equally if we are given a glimpse of their tortured insides, and the facial expressions are vulnerable while simultaneously resigned.

David Wojnarowicz was a US artist who created a body of Aids-activist piece of work, passionately disquisitional of the US government and the Catholic Church for failing to promote safe-sexual activity data. In a deeply personal, untitled self-portrait, he reflects upon his own mortality. About six months before he died of Aids, Wojnarowicz was driving through Decease Valley in California and asked his travelling companion Marion Scemama to finish. He got out of the automobile and furiously started to scrape the earth with his blank hands, before burying himself.

Every bit in the self-portrait by a influenza-stricken Munch, Dr Fiona Johnstone, a contemporary art historian from the UK, sees this work as David Wojnarowicz attempting to assert agency. "Hither David takes control of his own fate by preempting information technology, wrestling back command of his affliction by performing his own burial," she says.

In this untitled self-portrait, David Wojnarowicz reflects on his own mortality (Credit: Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York)

Today's digital platforms are enabling artists to respond to the Covid-19 crisis by expressing and sharing in real fourth dimension. The Irish-born artist Michael Craig-Martin has created a Thank you NHS blossom poster. We are encouraged to co-create the artwork past downloading it, colouring it in, and then collaborating past displaying it in our window.

Michael Craig-Martin is amidst the many artists who have been inspired by the current pandemic (Credit: Michael Craig-Martin)

In countries across the world, artists are slowly making sense of the coronavirus and the self-isolating response in countries across the world. Contemporary art historians will be eagerly awaiting their work. Nosotros who are living through this modernistic-day plague will engage with these emerging images; they might fifty-fifty regain some control over an feel that threatens and so much of humanity and our globalised lives.

Enquiry by Kate Provornaya

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else yous have seen on BBC Civilization, head over to our Facebook page or message usa on Twitter .

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Civilisation, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Fri.

cravenmosencestiss.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200514-how-art-has-depicted-plagues

0 Response to "What Effect Did the Black Plague Have on Art"

Post a Comment